Art Interviews

FROM STONE TO LINEN

An Interview for Cabana Magazine

Margo Fortuny speaks to Sergio Roger, an artist who reinvents classical sculptures in linen and silk.

Margo Fortuny: How did you first become interested in the classical world?

Sergio Roger: Five years ago, more or less, I wanted to challenge myself and see if I was able to replicate classical idealism through this unusual material (antique linen), because it has limitations with details you’re not able to reach. It’s always a negotiation between going into very fine detail and suggesting. That’s something I really like because classical art, and ruins, have been modified by time. Sometimes features are erased. It’s more about guessing… the absence, what is left, and so on.

MF: You combine sculpture with textiles. Is this a commentary on the intersection of masculinity and femininity?

SR: It does but it’s not intentional. On one hand, I’m talking about the permanence and solemnity of past Roman emperors and architectural elements, columns, friezes… Creating them in this material relates more to the sensitive world, to the female world, like stitching. I think the way I create it’s not the way you carve stone or melt bronze; there’s something very aggressive about that process. It’s like a fight against the material. The way we stitch, we sew, is an act of love. It’s very delicate; textiles absorb in a passive way, whereas stone does the opposite. Stone has an energy that actively spreads outside itself. That’s very masculine/ feminine in a way. It’s also very problematic. I don’t think masculine or feminine should be related specifically to sex. I think they are opposite energies, complementary. I don’t think it’s “men are…” or “women are…” It’s a bit like the Chinese philosophy of Yin and Yang, the opposite dynamic energies that in this case we call masculine/ feminine, but aren’t necessary...

MF: … as traditional labels?

SR: Yes, but in a way it’s also about breaking with that. Hopefully one day I’m going to do big pieces. To sew, in these monumental sizes, as something related more to the domestic world, the intimate world, of embroidering, doing cushions, quilts, but then making architecture is taking this technique to another scale, which is really fascinating. I love that. I think it’s very political.

MF: Tell me about your newest sculptures…

SR: My new work is large-scale, about two meters tall, and it’s all silk. For the first time, I introduce color and the new material. Taking the idea of our vision of classicism, distorting it, and giving it a more camp reading. I’m very interested in the history of fabrics and how we are connected: the social perspective, economic perspective, and how the production of fabric is connected to history, regions and times, geographically and historically.

What I’m doing… it’s from tradition but also experimentation. That’s how I see my pieces being on the border between craft and art, because I’m taking craft a step further. That’s probably what art is, taking existing ideas or materials and taking (them) somewhere else… somewhere unexpected or different.

GILBERT & GEORGE: ‘WHEN PEOPLE SEE US, THAT BECOMES PART OF THE IDEA OF TWO HUMAN BEINGS AS ONE ARTWORK.’

An Interview by Margo Fortuny for Wallpaper Magazine

As their ‘London Pictures’ exhibition marks The Gilbert & George Centre’s first anniversary, the artists talk to Wallpaper* of their early practice, daily routine, and what next.

Gilbert & George, first heralded for their performance piece The Singing Sculpture (1969), began their career with frequent appearances at parties, galleries, and art museums, acting as live sculptures, from the 1960s to the 1990s. In the variety of works they created, they erased the line between life and art. In the years since, the duo have focused on colourful, controversial pictures, often inspired by London’s East End. To date, they say, they have had more than 105 museum shows.

As their latest exhibition, ‘London Pictures’ runs at The Gilbert & George Centre, which they established in 2023, they remain, discreetly, as enthusiastic as ever. Wallpaper* joined Gilbert & George in conversation.

Wallpaper*: You met in 1967 at art school. What was your practice like when you started out?

George: Looking back, we knew that you couldn't employ two people as an artist and you wouldn't get a grant for two people in that way. We wandered the streets of London rather than looking for grants.

Gilbert: We were very lucky because one day we were standing in a corner of a room with our heads (painted) gold, and a person comes up and says, ‘I'm Konrad Fischer. Do something with me in Dusseldorf.’

George: That was the leading modern art dealer in the world. Within months of that, we were presenting The Singing Sculpture in Brussels, at a pop-up gallery, very unsuccessfully. Very few people came. At the end of the evening an old lady, she was much younger than we are now, came up. ‘My name is Ileana Sonnabend. I'm opening a gallery in New York and you must be the first exhibition.’ These two people, one picked us up for North America and one picked us up for Europe.

Gilbert: In 1968, 1969 we started sending out these postal sculptures. It's like an artwork by post. We designed pieces of work in an envelope and sent it to special people. We used to have the addresses of 400 or 500 people.

George: Konrad Fischer gave us his address list.

Gilbert: An amazing success.

W*: You have said, ‘Our whole life is one big sculpture.’ What are some things that you do to make your life a daily artwork?

Gilbert: First, I think, getting up.

W*: Just getting up, that's the most important thing.

George: We’ve always felt that we have a highly developed sense of purpose. If you’ve got a stall in the market you’ve got to have purpose: I’ve got the best shellfish.

Gilbert: When people see us, that becomes part of the idea of two human beings being one artwork.

W*: I've read that Kraftwerk was inspired by how you present yourself, how you’ve always worn nearly matching suits everywhere. Have you met Kraftwerk?

George: They did let us know that.

Gilbert: We never met them but yes, many people told us that.

W*: Do you ever listen to Kraftwerk’s music?

Gilbert: We don’t know what it is.

George: Music is the enemy.

W*: Is there any music you enjoy?

George: We don't have the equipment to listen to music.

Gilbert: We never listen to music.

W*: Never? That's very radical.

George: We don't like anything to take our brains into distraction.

Gilbert: We watch television at 6 o’clock for the news. That’s it.

George: That's why we go to the same restaurant every night and we never read the menu, because all of our friends are thinking which restaurant to go to tomorrow night. And when they get to the restaurant, they spend half an hour reading the menu before they have a meal. We try to keep operating, really concentrated.

W*: Focused on art?

George: Yes. On art and life. Death. Hope. Life. Fear. Sex.

Gilbert: Money.

George: Race.

Gilbert: Religion.

W*: What are you excited about right now?

George: We're excited because we're in the middle of creating a new group of pictures. We’re excited that we're doing [a] big Hayward show next year.

Gilbert: We’re very excited about being alive.

‘London Pictures’ is on view at The Gilbert & George Centre in London until the end of 2024. The artists’ 1974 book ‘Dark Shadow’ is back in print (available at Waterstones and Amazon)

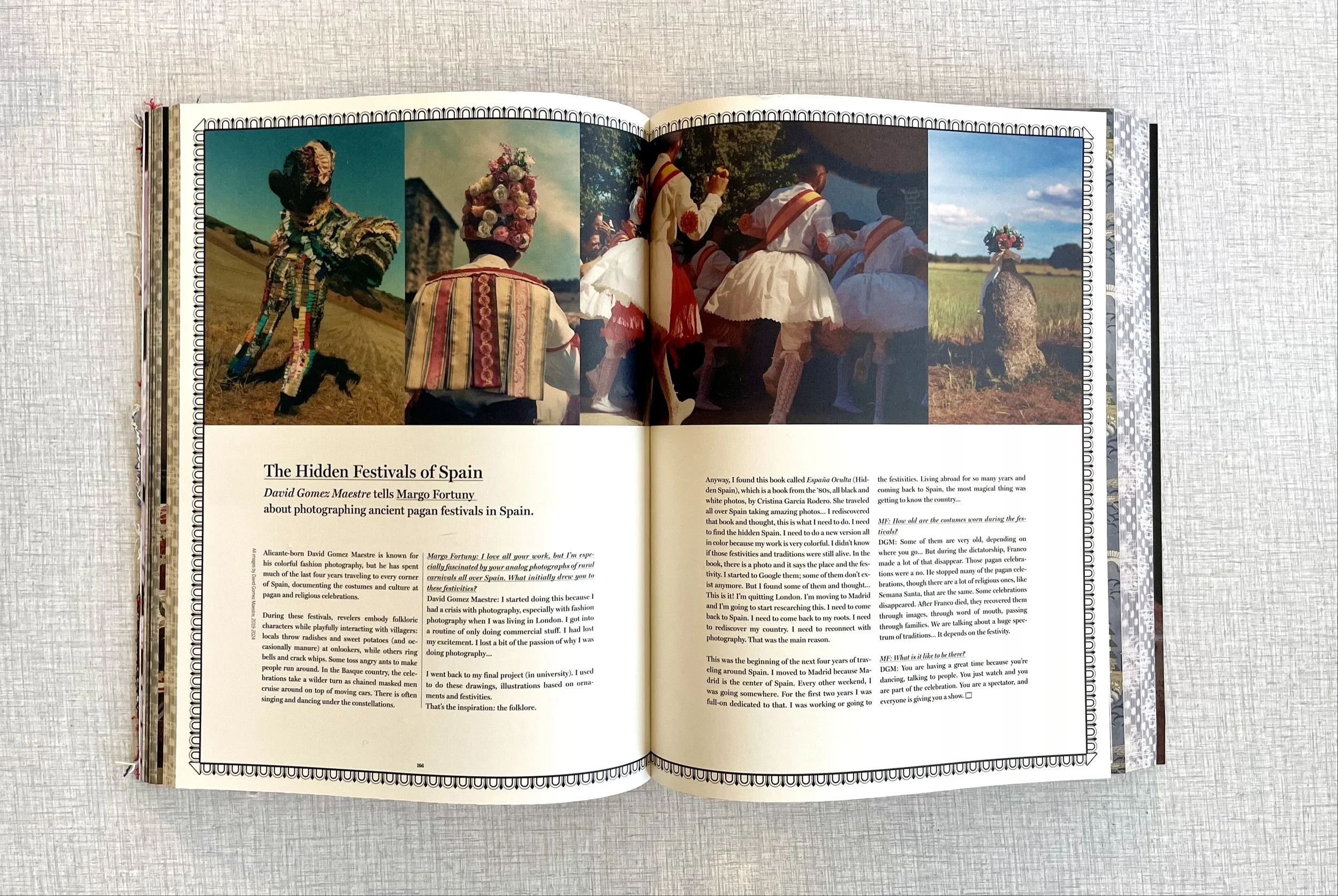

THE HIDDEN FESTIVALS OF SPAIN

An Interview for Cabana Magazine

David Gomez Maestre tells Margo Fortuny about photographing ancient pagan festivals in Spain.

Alicante-born David Gomez Maestre is known for his colorful fashion photography but he has spent a large part of the last four years traveling to every corner of Spain, documenting the costumes and culture at pagan and religious celebrations.

During these festivals, revelers embody folkloric characters while playfully interacting with villagers: locals throw radishes and sweet potatoes (and occasionally manure) at onlookers, while others ring bells and crack whips. Some toss angry ants to make people run around. In the Basque country, the celebrations take a wilder turn, as chained masked men cruise around on top of moving cars. There is often singing and dancing under the constellations.

Margo Fortuny: I love all your work, but I'm especially fascinated by your analog photographs of rural carnivals all over Spain. What originally drew you to these festivities?

David Gomez Maestre: I started doing this is because I had a crisis with photography, especially with fashion photography when I was living in London. I got in a routine of only doing commercial stuff. I had lost my excitement. I lost a bit of the passion of why I was doing photography… I went back to my final project (in university.) I used to do these drawings, illustrations based on ornaments and festivities. That's the inspiration: the folklore.

Anyway, I found this book called España Oculta (Hidden Spain), which is a book from the ‘80s, all black and white photos, by Cristina García Rodero. She travelled all over Spain taking amazing photos… I rediscovered that book and thought, this is what I need to do. I need to find the hidden Spain. I need to do a new version all in color because my work is very colorful. I didn’t know if those festivities and traditions were still alive. In the book there is a photo and it says the place and the festivity. I started to Google them; some of them don't exist anymore. But I found some of them and thought…This is it! I'm quitting London. I'm moving to Madrid and I'm going to start researching this. I need to come back to Spain. I need to come back to my roots. I need to rediscover my country. I need to reconnect with photography. That was the main reason.

This was the beginning of the next four years traveling around Spain. I moved to Madrid because Madrid is the center of Spain. Every other weekend I was going somewhere. For the first two years I was full-on dedicated to that. I was working or going to the festivities. Living abroad for so many years and coming back to Spain, the most magical thing was getting to know the country...

MF: How old are the costumes worn during the festivals?

DGM: Some of them are very old, depending on where you go… But during the dictatorship, Franco made a lot of that disappear. Those pagan celebrations were a no. He stopped many of the pagan celebrations, though there are a lot of religious ones, like Semana Santa, that are the same. Some celebrations disappeared. After Franco died, they recovered them through images, through word of mouth, passing through families. We are talking about a huge spectrum of traditions… It depends on the festivity.

MF: What is it like to be there?

DGM: You are having a great time because you're dancing, talking to people. You just watch and you are part of the celebration. You are a spectator and everyone is giving you a show.

MOVEMENT AND FLIGHT

An Interview for Cabana Magazine

Margo Fortuny speaks to the artist Zsolt József Simon about the influence of gymnastics on sculpture, seeing movement in everything, and how he creates work to fit into everyone’s lives.

Margo Fortuny: You’re known for your otherworldly ceramics, created in a slow, intricate process. Are your works inspired by things you’ve seen in real life?

Zsolt József Simon: Most of my works remind people of sea creatures, or something like that, but everything I build is based on ancient architecture. Maybe because of the technique, they seem like bones or sea creatures, but those things do not inspire me. I like ancient architecture, especially the columns from the Archaic Greek period. They are not exactly straight lines…and the kouros statues from Greece, and Romanic medieval carvings from Armenian and Georgian churches.

MF: In addition to studying porcelain painting, you’ve studied Bothmer Gymnastics and martial arts. Does physical activity inspire you?

ZJS: It’s mainly the concept of movement behind Bothmer Gymnastics, based on equilibrium, which is the strongest point of view in all my works…to always be balanced between extremes. I like the axis, the middle, stability. I see everything as a movement. I don’t look at the pieces as step-by-step; I see the past and the future of things at the same time. When I look at a vase I see how it moves. Is it extending or falling down or collapsing? Does it have some potential to be continued? So this is how I look at every art object. It’s more of an organic way of looking at things.

MF: Do you create art within a community or do you work more on your own?

ZJS: I work alone but I don’t want to make the pieces only for myself. I don’t want to make my work separated from the world. This is why I listen. I’m not that individualist artist just making what I want.

I would be blind and deaf without other artists. Art shouldn’t be just an expression; art should be something in between the artist and the audience. What I create is already out of me, and if something is out of me it’s already attached to the space filled by other people. The piece must fit in the space between two people. If most people ignored what I make, maybe I wouldn’t make it, unless I saw that it was really good. It’s very important to make a piece that fits other people’s lifestyle, not only mine.

MF: How much do you use visualization in your process?

ZJS: When I look at anything (unless I’m watching TV or a movie) my eyes always start creating a sculpture of what I’m looking at. How can I use that element in a sculpture? In front of my eyes, everything is alive…from the present position to a possible sculpture. Thinking is very fast. You can create everything in a few seconds, but the technique I use is a long process.

MF: What is the intention behind your sculptures?

ZJS: I have one aim in my sculptures: to feed the eyes with life and beauty.

THE HOUSE OF THE MIND

An Interview for Cabana Magazine

When Margo Fortuny met with the artist Carmen Mazarrasa they discussed how her work honors places by carefully recreating them in miniature as well as the magic of beauty.

Margo Fortuny: How do you create lost spaces from memory?

Carmen Mazarrasa: It’s a bit of everything. I have a lot of pictures. For the more personal ones I have journals and things that speak of a certain moment. It’s not only about recreating the space but the time. For my exhibition Lost Paradises, [that took place in Madrid] it explored not only the space that was lost, but also the moment. For me it is joyous, it’s a celebration; it’s not at all nostalgic. It’s an homage in a sense. It leaves things in peace in my mind.

One of the scenes I made was my bedroom when my daughter was small. It was a really beautiful house and it was a moment when everything was alright. Then everything fell apart. But I remember that sense of being all right.

MF: Do you ever create spaces that don’t exist?

CM: Sometimes I create spaces that don’t exist as a magical exercise. I was struggling because I didn’t have a workshop in Madrid. So I just built a third floor and put it on top of a dollhouse and started making the workshop there. I said, when I have the workshop in the dollhouse the workshop exists.

MF: And later you got a workshop that was similar?

CM: Not similar. I literally took the sofas out of the living room and started working in there.

What’s interesting about the work is all the technical development that it requires. Each time I see a new object I think, I’ll have to learn how to solder, or I’ll buy a small kiln to do ceramics. It’s trying out new things in a really small format that allows you to never master any skill fully but have loads of skills that you can use. I have a lot of fun in there.

MF: Suppose Patti Smith asked you to recreate the apartment she used to live in with Mapplethorpe, would you do that?

CM: Absolutely. I have a very strong connection to her writing and music. There are some spaces that really need to be created so as not to lose them. That’s my motivation. It’s about evoking the sense of people, their relationships with objects, their relationships with space and the thing they call home, and how that feels.

One of the projects I’m working on now is the workshop of a friend of mine who died a couple of years ago. He was this amazing creator of beauty. He was also a really bad hoarder. This piece is about the force of beauty that is lost from the world. There’s a part of it that feels unfair. The act of taking those places that mean so much and representing them is a really emotional and beautiful thing to do. It’s actually very cathartic. It works in a magical way, you make it and there it is and you can have it back.

THE AEROSOL OPTIMIST

An Interview with Futura 2000 by Margo Fortuny for Exit Magazine

Futura 2000 is a graffiti legend famous for an abstracted style of spraycan art. He has exhibited at the Tate Gallery in London, the Museo d'Arte Moderna in Bologna, the Picasso Museum in Antibes, and the New Museum in Manhattan, among others. Exit spoke to Futura 2000 recently about The Clash, his friendship with Jean-Michel Basquiat, and the New York art scene.

I love all those 80s movies about New York's early hip hop scene: Wild Style, Krush Groove, Style Wars...Were you in any of those?

When some of those movies were filmed I happened to be away in London with The Clash. When I came back I managed to sneak into Wild Style ; I’m in a scene in a club with the late Dondi White, and I’m at the end of Style Wars on the boat.

What was it like touring with The Clash?

That was an introduction to Europe and ultimately, that helped create a name for me. I didn’t know those guys when they came to New York. It was their scene coming here as opposed to,“Oh yeah, I know London Calling. I know Sandinista.“ I didn’t know any of that. I met Joe (Strummer), he was an amazing individual, almost like an older brother, a very deep man, an emotional guy. That was amazing to meet someone who was so well-known and very talented in his field. I got to sing on a record with the Clash called Overpowered by Funk, on the album Combat Rock. You know how things are when you’re in it and it’s all going on and you don’t really even know what’s happening? It was quite a little tornado. That was the most amazing experience of my life- at that time- short of meeting my wife and having children.

Did you hang out with Basquiat back in the day?

1979, ’80, ’81, ’82, those were the wonder years in New York when it all started to incubate. People like Jean and Keith (Haring) were more conscious of being artists, that was their thing. Graffiti writers weren’t educated like that. We didn’t think, Oh we’re getting into the art world. These kids, Jean, Keith, Kenny, and all the more famous guys of that era, Clemente, Schnabel, were artists. They were educated, and so for them to do what they did ultimately was not a surprise.

There’s so much revisionist history, people can say what they want... but Jean was a very good friend and he was part of all of it. I remember thinking, “Wow, he’s doing a very permanent thing.” And people said, “Oh, my kids could do that.” But no one understood he was interpreting Cy Twombly, and he was showing relationships in art, which is what the art world wants you to do. What he created gave it respect. It’s cyclical. He was a master. I regret that he killed himself through his addiction. Keith is another story. Warhol as well, I knew all of those people, though with Andy I was a little standoffish because I thought he was a pretty strange guy.

I remember Jean giving me a hundred dollar bill once. He sold some postcards, sort of like that scene out of the movie (Basquiat) He sold them to Bischofberger or Warhol, I don’t know, but he had a pocket full of hundred dollar bills, and he was like, “Lenny, here you go, get some art supplies.” I thought “Wow. But I really shouldn’t take this.” He said, “No, you have to, come on. When you’re doing well, hook up artists, man. Tell them to do work.” I was like, “Wow, thank you.” And you know, I went and bought some canvas, some paint, whatever. I’ll never forget that day. Just before he passed away a lot of people used his generosity and his openness. People would hang around his studio and drink, do drugs, people were taking advantage of him because sometimes he would get so fucked up I guess he needed people around. That Basquiat isn’t here is a real tragedy. Everything that he’s done and everything that’s said of him is all worthy. He was way ahead of his time. He was a brilliant artist.

How has your style evolved over the years? Is it more graphic or theoretical?

Yes, it is more graphic in a sense. You can’t really alter the aerosol medium as it is. It’s always going to be a quick dry response medium. It’s very workable. I like to think I’ve gotten better through practice but I’m still trying to discover what I really want to paint. I am returning as a painter now. All of my recent graphic art and design, I’m putting that on the back burner. In the last decade the movement has spun back around and now I’m getting caught up in this gravitational pull. It would be nice to get a little bit known in my own country, finally. My aim is to redirect traffic to other things I’m doing now. I made a lot of decisions for 2012. It’s gonna be a new me. I bought a suit. You know what I’m saying? It’s that kind of change in lifestyle.

So your fashion collaborations are over now…

I have bigger fish to capture. I’m holding back on all those other things that are not quite as fascinating. Right now I have some potential clients that are very, very big.

What kind of direction are you moving in? Galleries, public art projects?

I like public art more than galleries. The gallery I’m working with in Paris, Jerome, they’re amazing. However, I am looking at other ways of exposing my work and some of those could be public art. I’m trying to work with some hotels, and painting a private jet. I’m looking at art that doesn't have to be in a gallery. I want to do murals around the world as well. There’s Os Gêmeos and Shepard Fairey, Twist, I want to do something like that in the public view. Where can I take my work to reach a new audience? I think that’s the most important thing. Everything’s already starting to line up. I’ve got a book deal with Rizzoli. They’ve done Murakami, KAWS, but not until 2014.

When I was a kid I would write my name on the wall. Now I can figure out a better way to save my signature.

What artists inspire you or your style?

I would say that no artist has inspired me. I always try to find a negative space. When I first started writing graffiti I had a signature. Everyone did. But when I started painting I wasn’t looking at who was doing what. I was looking for what didn’t exist.

I’m influenced by life itself, whatever I’m exposed to. Because painting is an emotional experience it’s not like “Oh let me do a logo for Supreme,” where it’s going to be crafted and clinical. We know what they want, whereas with painting it’s more like “Let me show how I feel,” and based on my feelings that’s how I’m going to work.

Thirty years ago I was mad scared. I needed to know who’s Kandinsky, who is this, what is the Bauhaus movement... I never had access to that.

What do think of Banksy?

After this many years he’s put graff or street art on the map again in some commercial fashion. There’s a limit to how long you can be witty. I come from a different school. We don’t stencil. Yeah, I’ve always dug him as a clever kid very much trending, but I’m not drinking all the Banksy Kool-Aid. Everything else: the movie, all that, it’s a lot of hype. To the uninformed, or to the people 30 and under, they think he’s the greatest thing ever. They don’t have true historical perspective. They don’t know any better. I saw his show at the MOCA at last year. Your Banksy, your Jeff Koons, any other artist that has a team of people- it’s not my cup of tea.

It becomes a factory...

Totally. Warhol taught everyone how to do that. I don’t like that as much. Whereas if I go up to someone’s studio, like Space Invader in Paris, and I see this kid surrounded by work and it’s all him, all these creations worldwide, I appreciate that more. Don’t try to sell me a theatre. I don’t want a theatre. Give me a performance.

The thing about Banksy is that I don’t think I would be back in the art world if it wasn’t for him. I don’t want to come off bitter; I just want to be honest. I think the guy’s amazing but he’s lost it.

If I came to your birthday party and my present was a work by any artist, what would you want?

I would highly recommend you didn’t do that but if you were set on it I need a Michelangelo, a little sketch. The thing is I don’t live with art, so that would be one of the pieces I would have. Michelangelo, he’s my favourite.

What do you think of social media and art?

I’m in contact with KAWS. He’s commenting, I’m commenting back. But I don’t know if I’m talking to Brian (KAWS) or someone who works for Brian. It disturbs me that we’re creating all these buffers and filters between each other. It’s bullshit. I can be real in a place that’s very fake. That’s one of my missions right now. Because we’re living in a very fake world. It worries me. I’m very old school. There should be more interaction between us.

Do you think social media and apps help or hinder interaction?

Well, as a rule, I think they’re garbage. But if you want to go in and do something really interesting they can help. Obviously you can touch a lot of people.

What’s something you wish people knew about you?

At the end of the day, whether it’s a really nice hotel or restaurant, I’m more likely to be chilling with the kids in the kitchen than all the important people in the crowd... No matter what happens I hope people know I haven’t changed.

I've become what I wanted to do. Creating a family has been very important for me. I’m so grateful. In the 80s when things fell apart, ’85 when the house of cards that was the New York City art world crumbled, I thought, I predict that I’m going to live to the year 2000, so things were bound to get better.

I was very optimistic even though I was in relatively hard times. In 1985 you could put a tombstone on the New York scene- but there was another inspiration at that moment: my son was one years old. My children, my family, that’s been the support I’ve always needed. Finally, in some crazy twist, the stars are aligning again.

LONESOME ROADS: AN INTERVIEW WITH ALEC SOTH

Alec Soth has established himself as a prominent photographer through his distinct and subtle portrayal of places and characters from his journeys through America. Soth uses an old-fashioned 8 x 10 field camera, which takes long enough to set up to ensure the subjects are relaxed and the shots are deliberate. He shoots real people along forgotten roads, weathered landscapes, and colourful interiors. The photographs peel back perceptions of people, showing their individuality and a glimpse into their personalities. His gaze is empathetic, curious and friendly while keeping a respectful distance.

Alec Soth’s work is part of numerous collections including the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, The Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, and the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston. Soth has also exhibited at the 2004 Whitney Biennial and the Gagosian Gallery. Through January 2nd 2011, the Walker Art Center presents the artist’s first major U.S. survey exhibition.

This month EXIT spoke to Soth about escape, American culture, and the most beautiful thing he’s ever seen.

You've documented numerous individuals who have retreated from society. Have you ever escaped in a similar manner?

No, I’ve never retreated in any serious way. It’s just a fantasy. When I was a little kid, maybe six years old, I planned on running away from home. I packed my mom’s small suitcase and headed down the road. I probably only made it half a mile before my parents picked me up. The funny part of the story is that the suitcase was filled with books.

Most of my escape attempts nowadays are like everyone else’s: movies, books, booze.

There are echoes of Thoreau, O’Connor and Twain in your work. Who is your favourite author? To what extent does literature inspire your photography?

Flannery O’Connor was a big influence. In the beginning, in fact, the project was titled after a phrase from O’Conner…Black Line of Woods. I loved the way she described this line where culture ends and something raw begins. She has this really dark vision I’m attracted to.

But while this kind of serious literature informs the work, I’d say this project was even more inspired by popular literature. I’m a sucker for cheap paperbacks that play on this idea of the man on the run.

What do you think is the most interesting aspect of American culture?

Wow, that’s a huge question. I guess interests shift from one project to another. With Broken Manual, I was really attracted to the idea of the cowboy, the lone man who doesn’t need other people to survive in the world. There was something similar at play with Sleeping by the Mississippi, but it was less about self-sufficiency than this very general and confusing American hunger for ‘freedom.’

What attracts you to the middle of America?

I find it to be as rich and nuanced as any other place. I prefer to photograph in America because I understand it. I speak the language of the place. And while the language may not be flowery or steeped in history, I wouldn’t call it banal.

You used to have a list on the back of your business card and you've blogged about To Do Lists. Do you think people who write lists get more done?

While I’ve talked about the importance of lists for me, I probably haven’t emphasized the importance of brainstorming – just letting your thoughts run wild and seeing what comes out. Most of the lists I made are just a form of brainstorming. And the truth is that most of the ideas I jot down go unphotographed. But the list gets me out the door and moving in otherwise unlikely directions. And every once in a while I get lucky. Is there anything more satisfying than checking something off of a list?

I read this quote on your blog: the photograph “does its job stopping time. but mostly it is a charming reminder of the hunt.” What are you hunting for?

It really is a hunt. On one level it is a hunt for pictures. On another level it is a hunt to come to terms with my own longing. With Sleeping by the Mississippi, it was my longing to be a boy. With Niagara it was my longing for new love. With Broken Manual it was my longing for escape.

Who is the most fascinating person you have ever met? Did you have the opportunity to photograph that person?

I don’t want to sound corny, but most people are pretty interesting once you get down a few layers. Of course people with fantastic life experiences are fascinating. They can tell you about how they’ve traveled the world, eating exotic fruits and so on. But the person who has avoided all of that, who’s chosen to live in the suburbs and live a conventional life – they aren’t necessarily boring. You just need to dig.

One of the most fascinating people I’ve met was a fellow named Garth. He lives in the California desert. He is a sweet and gentle man. He told me that “in this life, God happened to make me gay.” He also told me that he’s never been with another man for more than a week. This, to me, is fascinating. And I did photograph Garth. But the picture of him wasn’t great. Photographs aren’t very good at telling these kinds of stories.

What is the most beautiful thing you've ever seen?

When talking about this kind of intense beauty, it is impossible not to link it to youth – to “the first time.” I remember photographing my girlfriend naked when I was 16. I remember being on a train in Provence during a very rare snowfall when I was 20. Great beauty is usually seeped in longing and nostalgia.

From Here to There: Alec Soth’s America is at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis through January 2. http://alecsoth.com/photography/ http://littlebrownmushroom.wordpress.com/

Words: Margo Fortuny, Exit Magazine

THE THINGS I SAW BACK THEN

Peter Uka is a Cologne-based Nigerian artist who speaks four languages and collects records. He paints lively portraits of the people he knew growing up in Africa in the 1970s and 1980s. His figurative paintings and colorful installations explore memory and cultural identity. This week he talked to METAL about art, jazz, afrobeat and creating work that takes you home.

Can you tell me about your process of making a painting?

My process usually starts with an idea, most of the paintings I do are bones from memories, a snippet of different parts of what I remember from my childhood back home. I left home when I was very young. I was 15 years old when I moved out. So the memory of where I come from comes back to me in bits and pieces. I start with the sketches. The sketches might end up in the final picture, or the painting might change along the way. Sometimes it comes out of stories. I could be on the phone with a friend who I know from way back when and I get a flashback and use that to create a picture.

Why did you leave home when you were only 15 years old?

I left to go and stay with my cousin and further my education. I came to Lagos on my own and moved around a bit. A couple of years later, I got accepted into the Yaba College of Technology. Before I had an apartment, I was sleeping in the classroom with a handful of other students. We loved to be all hands on deck. In the beginning it wasn't just passion, I didn't have a place to stay. Then I got a job; I got a place to live. But sometimes I still slept in the classroom because it was easier to work that way. I went to the academy and I could paint any hour of the day, clean up, go to work, take a nap, and get back to work. It was a traditional art school system. When painting from life, it was expected to be done perfectly. If they told me to go outside and paint a street the composition had to be perfect. That was the culture of the art school that I came from. Now I try not to focus on my craftsmanship; it's more about the painting that tells a story, the whole sum.

So, what brought you to Germany?

There was a competition organized by Goethe Institute Art Academy and a Nigerian German-based artist called Chidi Kwubiri, and I won the prize. The prize granted me (and a few colleagues) the opportunity to come and exhibit here in Germany. After meeting the professor Tal R, I applied for further studies and that's how I started at the art academy in Germany.

I've noticed a very cool seventies aesthetic in many of your paintings: the clothes, the vehicles and the color combinations. What attracts you to the seventies visually?

I'm a child of the seventies. (Laughs.) Growing up, that's how I remember my parents. They used to dress like that. I remember my father's way of dressing, those jeans, how they flare out at the bottom, his friends, hanging out. Most of my work is influenced by the things that I saw back then.

Is it a way of honoring that memory?

Yes. It's my therapy session. I'm a father now; I can't just sit there and whine about the things that I miss. Instead, I sit down and do something about it. I choose to do it this way.

Is that what you mean by therapy - you're taking action instead of letting it fester in your head?

Yes. I'm here now, painting these things but in the next three or four years I could be painting a different subject. Very soon, I'm moving towards more installation.

I love your bus installation work. What attracts you to installation?

I find it more appealing than most paintings, to create something out of nothing, to be able to make something to ponder. That's more interesting than just making something beautiful. I'm not chasing beauty. I'm chasing a conversation. Whether it's painting, installation, or sculpture, I would like for people to comment on it, to have a conversation. When that happens then I've achieved my goal.

That's interesting because a lot of your paintings are very beautiful to look at. Is that a coincidence?

Yes. The important thing is that the work gives you a reason to question things, to remember certain places and moments in time. I would like to get to that point where if you take the African figures out of my work the same subject matter applies to most cultures.

I want to take people to a time that either they've experienced, or they've heard others have experienced. Now the world has become a global village due to modern technology. Before, we were all experiencing the same things at the same time but due to lack of communication we were not aware of that.

When the hippie lifestyle became very popular in the 1960s and 1970s, Woodstock happened in America and everybody thought, that's just in America. But I remember at the same time there were a lot of hippies in Africa. The counterculture lifestyle was breaking out in other parts of the world too. Due to lack of communication, many people weren't aware of that. They thought it was exclusive to a particular place in America. But it wasn't like that.

Your portraits convey a specific style and dignity. What do you aim to communicate about the subjects of your paintings?

I realised that we are going through an identity crisis. I'll put it in the context of Black artists. Most Black artists are in an identity crisis situation at the moment. We are trying to identify ourselves first before we can take the next step. As a result, there's a lot of portraiture. We are showing ourselves, either consciously or subconsciously. For me, it's more about establishing who we are as people.

When I first came here (to Germany) I went to museums and I never saw a painting of a black person hanging on the wall. So where do I fit in? If my face is not visible on the platform, how do I fit in? That's what I was contemplating.

Then I stumbled upon the work of Kerry James Marshall at the Ludwig Museum near my house. I was blown away. I started asking questions. I came across an interview he gave. He experienced the same thing years ago that I was experiencing at that moment. This man already went through all that. He chose to do what he wanted. He took that bold step. This affirmed that my ideas were right. I had been too scared to put it out there. His work gave me the assurance to just be myself. I chose to do that. Then I did my first series of work in this area.

As my work progressed, people started coming to me and saying, have you heard of this person? Do you know that artist? I found out about people like Barley Hendrix two years ago, and more recently, the Nigerian artist Njideka Akunyili Crosby. There are other people thinking like me. We're just being unapologetically ourselves and not caring what other people think. We have to tell our own truth. I do believe that as a painter you can't tell anybody else's truth.

How did you overcome those initial doubts?

In the beginning I was worried about how the reception would be if I decided to paint this way, because everything I saw around me was the opposite of me. I looked around and saw one or two paintings of Black people but they were shown as the slave or the servant standing in the corner or the background. I had never seen them as the focal point in a painting at that point.

So I started from there. I focused on indoor studies and portraits and depictions of daily life in Nigeria. I began doing this body of work in 2015. In 2017, when I did my final presentation in the academy that was the first time I realised the direction I wanted to go in. [Being an artist] it's either this or nothing else. It's a way of life for me. I never saw myself doing anything else or working for anyone else. I came to the point where it wasn't about commercial success. If it were, I wouldn't have studied art. I would have focused on becoming an architect.

Tell me about your painting, Quiet Listening. Did you know the subject personally?

Yeah, he was the one who introduced me to vinyl. He had quite the collection back then: a lot of highlife, a lot of jazz, and a lot of rock n roll. I remember how he listened to music. When he played highlife, he was moving around, he was always bumping his head. But when he listened to jazz, he would sit down and cross his legs. He would lean back. You could see when he was getting into his own world. He introduced me to Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Dave Brubeck and a few crossover jazz instrumentalists. He was the one who introduced me to Fela Kuti's music. He was a diehard Fela fan.

How old were you when you met him?

I was seven years old.

So you had this kind of music education from a very young age...

That was around 1982. He was always playing Miles or Coltrane. He was my older cousin. He was already in his thirties.

Can you tell me about the music scene where you grew up? How does it inform your work?

In the 1980s one of the biggest Nigerian music stars came from my area; his name is Bongos Ikwue. He lived not too far from us. My dad, who's a self-taught artist, was the guy you'd call for sign-writing, painting, drawing. My father painted his house and I remember him taking me there. I saw Bongos practicing with his band. That changed my understanding of music. That was the first time I saw a live band, trying to create something new. So I began to pay attention to music and sounds. It has a strong influence on what I do.

In my painting, Quiet Listening, there is an LP on the shelf. Since I paint from memory, I decided to recreate one of Bongos' LPs, to have it there like when you have a collection of music. For me vinyl LPs are the best [thing] to collect. I try to add bits and pieces of what I like, what I'm interested in, into my work.

Do you like any contemporary Nigerian musicians?

Yeah, like most Nigerians, I like Burna Boy. A handful of his music, and a handful of Wizkid and 2face. I'm more into people like Asa, Adekunle Gold, Simi and Brymo.

Do you listen to music when you paint or do you prefer silence?

Sound is very important to me. I'm kind of old school, so I listen to jazz a lot. At the moment I'm into Coltrane, and afrobeat. I also listen to a lot of highlife music.

What’s highlife?

It's a traditional fusion of jazz, soul, ska, all mixed together.

Who's a good artist to look up to learn about highlife?

Prince Nico Mbarga, Victor Uwaifo, Rex Lawson, or Chief Stephen Osita Osadebe. Highlife goes back to the 1930s, 1940s. It became more pronounced in the 1960s and 1970s. I listen more to '60s and '70s highlife. You'd be surprised, a lot of Nigerian music from those days influenced the Black American music scene, and the Black American music scene influenced them. It went both ways.

I read that when Fela Kuti (the Nigerian musician) went to America he met up with the Black Panthers, and he was learning all about Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, and there was this back and forth exchange of information...

People like Fela changed everything. After studying music and traveling and broadening his knowledge beyond the normal scope of things, he chose not to follow tradition by singing the way that everybody else did. He created his own sound. That's the most inspirational thing you can do, be authentic, be your true self. He sang in his own way. He decided to tell stories but his stories were very political. He talked about the daily things that we as Nigerians face.

As far as Black people are concerned, Michael Jackson or James Brown or Bob Marley... none of them can rival Fela. Anywhere you go in the world everybody knows Fela. That tells you how much impact he had as a musician. His story doesn't just apply to Black people. If you take the Black content out, people feel the same things in other cultures too, in a different way. For me, he is one of a kind. Fela is right up there among the greatest of all time.

What do you think about the cross-influence between Nigerian music and American music?

When a traditional musician travels abroad they see things hear things and bring them home. At the same time, when those musicians are playing abroad, they're inspiring local musicians. So we influence each other both ways. There are certain musicians who traveled to Africa at some point in their career. The music they made after that is clearly different from what they used to do. It's not just music; it also applies to the world of painting. There are painters who changed the dynamics of how they approached their work after studying African art. Sometimes they changed everything.

Like Picasso?

Yeah, and a handful of others. In this day and age, everything is so open and you can see a direct comparison between a work and where they took it from. Back in the day, people didn't know where painters got those ideas from because that information was so obscure. So people saw those artists and said, "Man, he's a genius!" Now when you put these works side by side, you see the influences. I'm not trying to diminish what they achieved. They did something great because they brought exposure to African art. They made the world aware of it. That's wonderful.

How do you define home?

Home is where I come from. I do miss it when I talk to my family and friends. That comes back to what I do now. The reason I do what I do was born out of that, the fact that I miss it so much. For me, I create a fantasy world of revisiting the past. I revisit certain things, certain scenes, the things that I remember.

Everybody that I know, and how I remember them, [they have since] changed. Everybody I know now has a family, is a father or a mother. We've all grown up. My memories of most of these people are from when I was a teenager. That's how the picture is in my head. So when I see them now I try to reconcile the past with how we have all moved on with our lives. I'm filling that gap by creating paintings of how I imagine them to be. Some of my works are based on that time lapse and the things that I remember: where I used to play, the older people around us, how they carried themselves back then. I try to recreate them in my own way. When I have these paintings around me they take me back, as if I'm home. It's right there, like nothing ever changed. That's the way I remember home.

Peter Uka is exhibiting at the new Mariane Ibrahim gallery in Paris in September 2021. Peter Uka's next solo show takes place in November 2021 at the Mariane Ibrahim gallery in Chicago.

Margo Fortuny, Metal

HE DOESN’T BELIEVE IN MUSES, HE BELIEVES IN LINDSAY LOHAN

An Interview with Richard Phillips for Exit Magazine

Manhattan-based American painter Richard Phillips is famous for his hyperrealist portraits of celebrities and beautiful women. He also creates imagery for album art and luxury fashion brands. Is it contemporary Pop Art? Or an exultation of the commercial? In addition to his recent show at the Gagosian Gallery in New York, Phillips has exhibited at numerous biennales and museums including the Tate Modern in London, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and the Whitney Museum in New York. EXIT met up with Richard Philips to discuss his work, surf films, the concept of the muse and the detachment of the artist.

In your recent paintings, California’s myth is as much a subject as the starlets. Why California?

As somebody who grew up on the East Coast and has lived here all my life, California represents the ideal, a fiction. It really is an alternate reality. It’s one that’s all-consuming and intoxicating. Even the healthy sunshine beauty of it has a certain element of intoxication. I feel like I’m constantly missing California, even though I’ve never lived there.

I think of London as a partner, as a place I need to be to do my work and California is like a lover, more like a fantasy, somewhere I probably shouldn’t be all the time or I would just sink into a swimming pool of endless hedonism, you know?

Yeah, that’s the way I probably should’ve answered your first question. That’s exactly how I feel. If I moved out there, I would just surf and not make any art. Frankly I don’t know how people do it. I have dear friends that have made it work on an amazing level. But I would just succumb, trip out, and not do anything.

It happens! …Do you have a favourite muse, someone who has inspired you the most?

All the work I’ve done has brought up the question of the muse. I think a muse suggests someone who is subordinate and or being used in a passive position with their creation to the artwork, that somehow the artist has some kind of divine capacity to translate what’s going on, and the muse somehow inspires him to other levels. (With my work) it was much more specifically: hey, we’re working together, how are we going to create these images. This is what we’re hoping to accomplish, this is what we’re trying to do. It was really a repudiation of the idea of the muse more than anything else. Although the language of the imagery alluded to it, the working of it couldn’t have been further from the notion of the traditional sense of the muse.

In ancient Greece, the muses were these quasi-goddesses who gave the artist the gift of inspiration and knowledge. It seems more like a recent idea that the muse is subordinate.

In modern art the common meaning of it would be: “Oh, so-and-so is your muse and just inspires you” I don’t adhere to that type of logic. Or the idea that art somehow is given to me by some divine power. One of my favourite paintings of all time is a Sigmar Polke painting ‘Divine Powers Told Me To Paint the Upper Right-hand Corner of this Painting Black’ It’s as simple as that. There is no divine intervention. It is an agreement between people who make art and how they do that, collaboration.

Why did you pick Lindsay Lohan, Adriana Lima, and Sasha Grey as subjects?

A lot of it was serendipity and having things just fall into place out of thin air. I was fortunate to have friends in contact with them, who made them aware of my work and encouraged them to consider working with me.

Are you trying to reveal aspects of their personalities? Or is it more an exploration of the superficial?

I think it’s both. Those are good observations. The images were selected based on the stills that were the most popularly used images in the media to function as placeholders for the films themselves. So the psychology for each of those pieces tended to be the one that connected the most with a large audience, in some cases, with millions of people. So it was an inversion of the idea of popular art: where the art references something and then it becomes popular. These images were already out there in the media before they were paintings.

Is there a goal for these specific paintings? Are they supposed to excite people, inspire lust, or are they a distraction from reality?

The intent was to focus on capturing these moments that had psychological intensity that related to the films, but could also be viewed independently. It was exploring that relationship with media, not only in the form of a show, but externally to the show as to what each individual carries with them… It really has a lot to do with verifying one’s own corporal presence. Paintings have the ability to do that because they’re kind of overwhelmingly large. In the rooms, you have these fleeting images rushing by you, and the paintings are nearly the same scale, but in a way they seem bigger than the films because they’re not moving… They’re very much empowered forceful images.

Would you say your paintings have the power to cause a physical reaction?

I’m very detached in a way. The way I paint is almost more of an engineering process, like building an apartment building. You have to have all the stuff in order and do it a certain way. To the degree that they function in any type of sensual or erotic sense is quite abstract to me. To produce a physical reaction in terms of how people relate to them, yeah, that’s obviously a goal. Then again, it’s entirely subjective and it remains abstract.

Do you ever get artist’s block and how do you deal with it?

I’ve never experienced that in any traditional sense. There are always different methods for arriving at potential work. I don’t make a lot of versions of work. I literally just make as much work as necessary for each exhibition.

Your film ‘First Point’ has been described as “surf noir.” What are some of your favourite surf films?

Well I had the great fortune of working with the most respected and talented contemporary surf filmmaker Taylor Steele and he was my co-director on all the films. His first film, Momentum, featuring Kelly Slater, was generation defining. Another was ‘Free & Easy’, which was an underground film from the 1960s that was the counterpoint to ‘Endless Summer’

Do you see a link between the surfer and the artist?

Most surfers that I know are also artists, including the one that we were very fortunate to use for surf sequences in the film, Kassia Meador, who’s also an artist, photographer, and designer. There is a direct link between the language of surfing and to that of fashion and various visual art forms. Art, celebrity, commerce, and sponsorship are often intertwined.

Would it be accurate to say that on one hand your ‘Most Wanted’ paintings (at White Cube in 2011) were critiquing these lucrative relationships, but on the other hand they were profiting from the phenomenon?

I think that there is a great a deal of confluence between those various forms. With my ‘Most Wanted’ show, I decided to put down on the canvases the very things that are, at this point, in need for verification. That was celebrity endorsement and luxury sponsorship. So each of the paintings had a young actor as an endorser and a sponsor’s logo on each picture. (Thus) you bring it to a broader population. Whether it actually functions as an artistic statement or not, I think that’s for the public to decide.

DRAWING HOOKS OUT OF YOUR THROAT

An Interview with Stanley Donwood by Margo Fortuny for Exit Magazine

Stanley Donwood is an English artist and writer who is famous for designing Radiohead’s album artwork. He has been collaborating with Thom Yorke for almost two decades. Donwood runs a studio called Slowly Downward Manufactory and he regularly exhibits his distinctive linocuts, paintings, and drawings in galleries around the world. When not creating visual art, he writes dark but lively prose. EXIT met up with Donwood before his recent show at the Outsider’s Gallery in London to discuss the next Radiohead album, Thom Yorke, writing, and how temperature affects art.

The next Radiohead album is described as a newspaper album with tiny pieces of artwork held together with plastic. What was the inspiration behind the design?

I’ve always really loved newspapers, their tactile quality, that crappy paper. Newspapers are on their way out. I like dying media. They have a poignancy that I don’t find in things like Twitter. But maybe when Twitter is dying maybe the last Tweet will be the saddest thing we’ve heard for years. The last daily newspaper we can buy will be an impossibly sad thing. So I wanted to use the format of a newspaper because a newspaper doesn’t pretend to be anything other than of the moment. Because a newspaper is so ephemeral that if you leave it out in the sunlight it will decay and go yellow and if you leave it out long enough there will be nothing left. (For this album) I wanted to make the opposite of an archival quality coffee table book. No future.

What’s Thom Yorke like? Is he quite serious? I read that when you collaborate one of you does something then the other destroys it. Then you mend it back and forth.

It depends on the time of day. We get on very well. We haven’t had an argument yet in twenty years. We just destroy each other’s work and then keep working at it. Keep battling until you get to the point where the conflict is resolved and that’s the end. We both like it after a lot of toing and froing.

Do you find English weather and temperament inspirational or limiting?

I don’t know. It’s an interesting idea. My dad always said the reason why the industrial revolution happened in England was because it’s so miserable that people are just desperate for something to do… There’s something about the pessimism that when I’m not here after a while I miss it. I really like the Mediterranean and California, places where it’s sunny and nice. You can do nothing (there.) I love it. Essentially I’m extremely lazy. Something in the appalling weather in this country forces me to go do something… to keep warm, half the time.

I agree. I’m so much happier in warm weather, but it’s hard getting anything done.

Exactly! But what’s the point of getting anything done? It’s natural to not do anything.

I thought, I’ve got some books in my head; I should go somewhere cold.

If you want to be miserable, go to Scandanavia. (He jokes) I’ve got this weird fascination with Scandinavia, places like Sweden, Norway and Iceland. I’ve never been but I’d like to go. Just to see what would happen. I’m really interested in snow, whiteness, and the idea of where the land and the sky blurs. Like when you’re on a boat and there’s really bad weather and you can’t see what’s the sky and what’s the sea. I imagine it’s like that in Northern latitudes. Is that snow falling or settling? It correlates with your mind. You don’t know what’s up or what’s down, what’s far or what’s near.

Is bleakness required for good art?

No, though I see what you’re saying. I really like the Aboriginal art that is done in a very bright, sunny environment, and all those dots and dream paintings. That very colourful style of painting. You also get that with the French Impressionists when they were down in the Southern regions of France…and the Fauves, they were called Wild Beasts. I didn’t quite understand it until I went down to some of the towns where the Fauves were. They were doing this artwork that was very bright, messy and amazing. I got there and after a few days I realized why you would make work like that because that’s how you feel. Bright, messy and amazing. There’s nothing wrong with that. I like that. Where I come from, artwork is more didactic.

To what extent does art history and political history inform what you’re doing now?

Probably a lot more than I think. Art history is something that I’m incredibly ignorant about. I went to Art College but I was sufficiently arrogant to not go to any of the lectures about art history, little bastard. Since then I’ve started to learn about art history and political history. So I’ve read lots of books about it and it’s made me realize how little I actually know. The certainties I held when I was 20 are now uncertainties at the best, vagrancies at the worst. Vague ideas.

There is a lot of writing on your website. Do you spend more time writing or doing visual art?

There is some kind of weird lock in my brain if I can’t work visually. I spend a lot of nights not being able to think then I start thinking I’m really shit, I should stop and get a job. That’s when I’m really low. I can’t do any visual artwork and that’s when I write, usually quite late at night. Then the other thing happens. I think what I’ve written is atrocious and despicable. Then I start doing artwork again. I can’t do the two at the same time. It’s impossible. It’s over a couple of weeks. One will fail and then one will emerge. Writing particularly is like drawing fish hooks out of your throat. It’s horrible. But necessary. Because you can’t leave them there.

Radiohead’s album with artwork The King of Limbs is shipped out on May 9th, 2011.

PURPLE RAIN

An Interview with KR by Margo Fortuny for Exit Magazine

"KR" a.k.a. Craig Costello grew up in New York City in the 80s at a time when the urban landscape was in constant flux. KR started as a graff writer and street artist. He studied photography and conceptual art, while continuing his original methods of creative expression. KR developed a recognizable drip down style with homemade supplies. Around the year 2000, the Lower East Side store Alfie began selling KR’s paints, which became KRink. It was a success and snapped up by boutiques around the world. Collette in Paris sells the markers and paints and features him on the website. Kidrobot, Burton, Levi, and other major labels have asked him to collaborate. Simian Mobile Disco namechecks him in the song Audacity of Huge, alongside high culture references James Joyce and Damian Hirst. CNN and The New York Times reported on his work. KR became a multimedia professional and has branched out into product design and gallery exhibitions. KR achieved the dream of making your art into your job.

EXIT magazine met up with the artist to discuss work, recognition, crack, culture, and New York.

Your large-scale works have an epic feel, like a street Abstract Expressionism. What's the inspiration behind them? Or is the action the concept?

The action is a part of it for sure. Abstract expressionism does play a part, as do color and mood. My work is influenced by my interest in contemporary art and my time writing graffiti; it's a combination.

What artists have inspired you?

Anish Kapoor, Rachel Whiteread, Chris Burden, Ellsworth Kelly, Tony Cragg, Jack Pierson, Sue Williams, Wolfgang Tillmans, Cy Twombly…The list goes on and on. I really enjoy contemporary art; it’s so diverse.

Would you consider Basquiat to be part of New York’s graffiti history?

Why not?

Who are your all time favourite legendary NYC graff artists?

There are so many subtleties to graffiti. Cost and Revs for their innovations and style. Seen for that classic 80's flavor. I love a lot of the 70s stuff: Stitch, Phase 2, Blade, Comet. Street bombers Joz, Josh 5, Easy, Veefer. Roaches did the most amazing train insides ever. And Reas for his natural flavor.

Yves Klein dragged nudes through blue paint to orchestral accompaniment, Richard Serra threw molten lead around galleries, Anish Kapoor’s cannons shoot paint onto museum walls…how do you see yourself in line with them as a contemporary artist?

All three are major influences and I love their work. I'm very flattered to even have someone mention these artists in relation to my work. They are accomplished professional artists, while I am merely trying to keep the cable TV on.

How important to your work is live performance/the act itself of painting?

Because of my history as a graffiti writer, it's sometimes difficult for me to come out of my shell. Live performance is not something I am interested in at all. Writing in the streets is really private, the idea is not to be seen at all, and if I do write in front of people, it is often a judgment of them and that they won't say or do anything.I feel there is definitely a performance aspect to writing and to art. But for me it is not a spectacle. I prefer to paint privately and show images.

Graffiti writers look at the work and also contemplate the process. If it is on a roof, it's interesting to see how someone got up on the roof. There is cleverness to the craft.

Back in the day, what was the craziest place you've tagged?

It's not so much the place as the situations. Graffiti can take you to ugly and interesting situations. I was waiting to write on a truck; dark alley, bad neighborhood. A man and a woman approached me. I showed them I just wanted to write on the truck. It was all good. She sat on the bumper and sucked his dick while he smoked crack and I did a fill in. I could hear her sucking his cock while I was painting. I snapped a quick pick when I was done, and that, was that.

A lot of Graff artists strive for recognition and you’ve expanded beyond that, you’ve gone from underground graff writer to overground commercial success. How much street art do you do these days with all your other professional commitments?

It's rare for me to be doing anything on the streets. I absolutely love the public space and think it's really important, but I have a lot of responsibilities, which makes it difficult for me to find time for making work in the street. I hope in the future to arrange more public work.

You’ve proven yourself as a master of exterior decoration. Do you do much interior design? Do you have plans for KRink wallpaper?

No plans for KRink wall paper. I have done some things in interiors, galleries, etc. I like it all.

I was reading your piece on Moscow on the blog (12ozprophet.com) how Moscow as a city still has a strong local flavour and identity in the face of globalization. What other cities do you find inspiring at the moment, in terms of edginess, creativity, and preserving a local feel?

I need to travel a bit more. A few years ago I went to Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam. I found it so interesting to be in places that had been cut off from western influence. I really enjoy nature and cultural experiences. Western cities are becoming so similar. I've never been, but I think Brazil has had a lot of really interesting things going on.

Early 80s movies like Style Wars and Wild Style depict New York as a different place. Growing up there, what do you think are the biggest changes the city has gone through? Has its culture been sanitized or supported with the economic development?

It's such a mixed bag. I don't miss the crime, the fear, and the destitution. But I do miss the flavor, the freaks, the creativity, the D.I.Y.ness… There are many native New Yorkers that complain about this and that and want the "old" New York. But in the end NYC is constantly changing and you have to adapt, or else end up being the annoying older guy always talking about the past. For sure, I have a ton of love for the natives who didn't move here to be hip and cool; I'm from Queens. But I also love everyone who moved here because they have the balls to try to make it happen and are willing to sacrifice and work hard and do whatever it takes. Both are an inspiration.

THE MAN WITH KALEIDOSCOPE EYES

An Interview with Alan Aldridge by Margo Fortuny for Exit Magazine

Alan Aldridge grew up in East London and moved to Los Angeles 28 years ago. In his early 20s, the young artist went from unemployed and unknown to a designer at the Sunday Times in four months. At first, he received hate mail for his unconventional depictions. Aldridge became the art director of Penguin a year later. Soon after, he was illustrating for the Beatles, drawing posters for Warhol, and hanging out with rock stars. Aldridge created album covers for the Who, Elton John, Cream, and the Rolling Stones. He also made successful children’s books filled with colourful beasts. Film deals, beauties, and traveling around the world factored in along with creative output. Aldridge is currently writing a book called Pandemonium, which is out next spring. Now the cult artist has a retrospective at London’s Design Museum. The exhibition covers his career as an artist, an illustrator, a graphic designer, art director and filmmaker. It includes Aldridge’s psychedelic designs, a hand-painted car, a hand-painted woman, photographs of John Lennon, and his seminal book The Beatles Illustrated Lyrics. I met up with the charming man in Soho to talk about his past and thoughts about the future.

When did you start drawing and designing?

We’ll get one story straight. I wasn’t good at art in school. In fact, one term I came bottom in the class. When the teacher read out the results, I kept thinking he would call my name out next, but no, it was so-and-so, and then so-and-so, “And last of all, Alan Aldridge, 3/100.” He glared at me; he thought I could do better than that. I mean, I wasn’t really trying, so he said, “Aldridge, you would’ve gotten 4/100 if you’d spelled your name right.”

I didn’t start drawing until my 20s, and that was drawing in bars, trying to sell portraits and they were all terrible. Never sold one. Then I went to a graphic workshop, because it said Free Coffee on its flyer, which I thought was really weird, ‘cause the flyer was in a coffee shop, so I went and it turned out to be a class for graphic design. I convinced the guys that ran it that I was broke and they let me sit at the back. It was a ten-week course, twice a week. Slowly I got into it and finally I won the big prize, to do a Penguin book for twenty-five pounds. Very quickly after that, Germano Facetti who was head of Penguin’s design group started giving me work and one of the jobs he gave me was a book called Private View by Lord Snowdon so I had to go to the palace. I became very good at putting layouts together. At the end of the gig, Lord Snowdon recommended me to the Sunday Times, which at that point had one of the best design groups in Europe. So I go along to the interview and I get the job. I had gone from literally nothing to the Sunday Times in about four months. I was only been there a year when I became art director at Penguin.

How did you shake up the place when you were designing the Penguin book covers in 1965-67?

Well I was made art director, so I was the boss. It’s a funny story-I was getting to have a reputation and I had done some Penguin books because I had won a prize with the graphic workshop. I won first prize to do a Penguin cover and the art director at Penguin liked me so much he gave me two or three covers to do a week. Then the boss at Penguin, a guy called Tony Godwin said, “Alan, you’re kind of trendy and know everyone. Do you know somebody, an American, to take over as art director of Penguin?” I said “Yeah, I do know someone, ME.” And he laughed and I laughed cause it was kind of a joke to think you could be only a year at Sunday Times and then become head of Penguin Books art department. I forgot about it and then two weeks later, he called me up and said, “Do you still want the job?” I said, “What job?” And he said, “The art director of Penguin.” I said, “Are you kidding me?” He said, “No, it’s yours.” I was twenty-three or twenty-four at the time. I had only been in the art business for two years, three at the most. Suddenly I was art director of Penguin and I brought my friends in to do the work in the studio. I started to get photographers and designers involved. We threw out the old grid; it was good fun.

Your Chelsea Girls poster is famous. How did you first get to know Andy Warhol?

He didn’t ask me personally. There was a place called Arts Lab in Covent Garden, which is a real bohemian, existential, beat generation kind of a joint. They were putting on the Chelsea Girls premiere. Somebody at Arts Lab called and told me Andy Warhol had asked if I’d do the poster, something like that. The poster became more famous than the movie.

Do you see any parallels with the creativity and upheaval of the 60s and the current cultural climate?

No, the difference between the 60s and now, is that the 60s already broke all the barriers: graphically, musically…if you listen to 50s music and the transition into 60s music, it was partly a drug culture as well which took over. There was colour in magazines-colour became prevalent, as opposed to black and white magazines. It was like the whole younger generation wanted to try out everything- and did. Today it would be very hard to say your vision is unique when so much has already paved the way before you. My drawings had no precedent in the 50s or early 60s. I drew whatever came into my head and I guess that, in its own way, is revolutionary.

I know a lot of people who are obsessed with the 60s and particularly influenced by the style and music of that time. It’s as if there is an imagined nostalgia for a superior era.

Well, 1967 was voted the year of the century, primarily because of Sgt. Pepper. The 60s are all about free love. I mean, I didn’t see too much of that…there were a lot of concerts, a lot of drugs, people were taking their clothes off. That didn’t happen in the 50s…Some of the Pop Art was spectacular.

Is there anything left to discover?

Oh yeah: computer art. You see what kids are doing in Photoshop. I find it very creative but it’s also cold. It’s almost like no hand has ever touched it. It’s very technical. I think my stuff has a bit of spirit to it.

Do you think there will be a mold-breaking creative time in the future?

We are coming up to the end of what is called the Darkest Age, and the Aztec calendar is 3,600 years long and it ends on 2012. Now some people read it apocalyptically –it’s going to be the end of the world- but as others read it, there’s going to be a new consciousness that could save the planet. Because the planet does need saving. So in 2012 I would bet something quite amazing is going to happen. I don’t know what. I don’t see any signs of anything else happening.

Do you listen to music when you work?

I have an itunes electronica channel on all the time: XTC. It’s techno mostly.

What is your favorite book?

Breaking Open the Head by Daniel Pinchbeck. It’s about Shamanism and the effects of psychedelic drugs.

What do you think is the most mind-expanding art out there?

It really depends on the viewer I think. I once when to Ghent in Belgium to see the Jan van Eyck altarpiece, the triptych, and nothing has every blown me away quite like that. At the same time I could look at psychedelic art and feel far less tripped out by it because it’s something I can understand. Jan van Eyck’s paintings don’t seem human to me. It was something that said to me; technically you can get a lot better if you try. He was a genius.

Then I suggest playing Exquisite Corpse. We whip up some pictures of hybrid creatures while he regales me with stories about when he was a teenage butcher and old East London. Back when Shoreditch was the roughest part of London, the pub Dirty Dicks used to have dead cats nailed to the wall. But Shoreditch has changed; they took the cats down and Alan Aldridge hasn’t been back since.

‘Alan Aldridge - The Man with Kaleidoscope Eyes’ is at the Design Museum, Shad Thames, London, SE1 2YD from 10 October 2008 to 25 January 2009.

STREET ART TO POP ART AND SNEAKERS IN BETWEEN

An Interview with KAWS and curator Mónica Ramírez-Montagut by Margo Fortuny for Exit Magazine

Brian Donnelly, a.k.a. KAWS, is an artist and designer based in New York City. As a teenager he skateboarded around Manhattan and New Jersey creating street art and intervening on advertising billboards. These playful reinterpretations of the images were so appealing that people started taking them home almost as soon as they went up.

KAWS’s art is both light-hearted and dark. He subverts pop culture symbols by adding unusual details or altering their features. He blurs the line between art and media, thus encouraging the viewer to redefine their definition of contemporary art.

KAWS moved on to detailed paintings and developed toys and statues. He set up a boutique in Tokyo, OriginalFake, where he sells his highly collectable work. Soon brands like Marc Jacobs and Comme des Garçons got involved, and stars such as Pharrell Williams and Kanye West were calling for collaborations. Now the art establishment is taking notice. Recently KAWS had solo shows at the esteemed Honor Fraser Gallery in Los Angeles, Galerie Perrotin in Miami, and Gering and López in New York. This summer The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Ridgefield, Connecticut, presents an exciting mix of KAWS’s classic works with his newest paintings, sculptures, and design objects.

EXIT spoke to Mónica Ramírez-Montagut, curator at The Aldrich, and then Brian Donnelly himself, about KAWS’s exhibition and the fine line where consumerism and culture meet.

What first attracted you to Brian’s work?

When we visited Brian’s studio we thought we were only going to see paintings and sculptures, so we were very surprised to see the vast output of different products that he had made. All were extremely well crafted technically and conceptually. His creative impulse towards everything struck us as very interesting.

How does his work celebrate and criticize consumer culture at the same time?

For example, he created these huge plastic packages for the large-scale canvases. If you come from a teenage culture of toy collecting, Superman, Planet of the Apes, you know you should not open the box. The moment you open the package the value goes down. Playing on those kinds of rules, he’s bringing that kind of collecting mentality into the art world. It’s brilliant. It had never been done in this plastic blister packaging. It’s a young adult sensibility and an awareness of consumerism.

What about his more corporate collaborations? How does that fit in?

KAWS got his business training in Japan with a lot of designers he started working with ten or 15 years ago. Working with these Japanese fashion labels, he saw that collaborations always test boundaries. It’s fun because there is a level of unpredictability. There is a dance around what is going to be the final product. If the relationship is well developed, it’s a win/win situation. With these corporate partnerships, he provides a fresh take on the product, but he also learns a lot in the process.

Do you think he’s alienating some art critics by “selling out”?